PART 1

This is the first of two posts about the life of John Hudson Robbins (1833-1912), a native of Decatur County, Indiana, who moved as a child to Missouri and Iowa, from where he set off for Oregon in 1862. The second post will discuss John’s varied life once he arrived in the Pacific Northwest.

Born in 1833, John Hudson Robbins was the son of John and Eda (Sanders) Robbins, and a grandson of Absalom and Mary (Ogle) Robbins. John and Eda had twelve children (John Hudson was number eight), who were born between 1819 and 1843, and from Henry County, Kentucky, to Monroe County, Missouri.

John Hudson Robbins was in Davis County, Iowa, at least by 1850, where he is recorded in the federal census. His mother died soon after, in 1854, and his father, John Robbins, followed not long after in 1857, leaving John Hudson without parents by the time he was 24 years old. Most of his siblings also lived in Davis County, though several stayed in Missouri and there was quite a lot of travel back and forth between the two areas. John’s oldest brother, Marquis Lindsay Robbins, emigrated to Oregon in 1853. John and his family were to follow in 1862, while two younger brothers Moses Riley Robbins and Samuel Robbins were to follow in 1865.

In 1854 John was married to Hester Elizabeth Minnick and the couple had three children prior to making the trip to Oregon. At the time of the trek, John and Hester’s children were Sarah Jane (age 7), Emma (age 3), and Benjamin Franklin (age 1½). Hester was expecting her fourth children when they left Iowa. In preparation for the trip, the Robbins’s grafted apple and cherry tree stock and visited relatives for the last time.

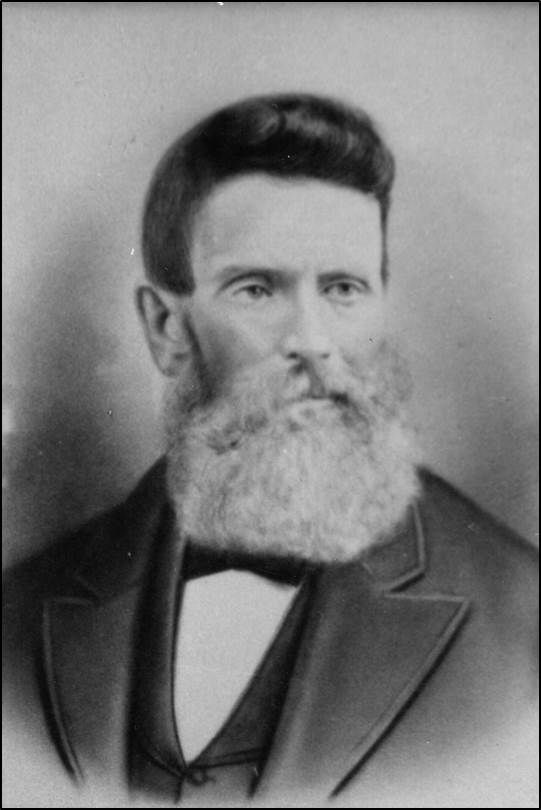

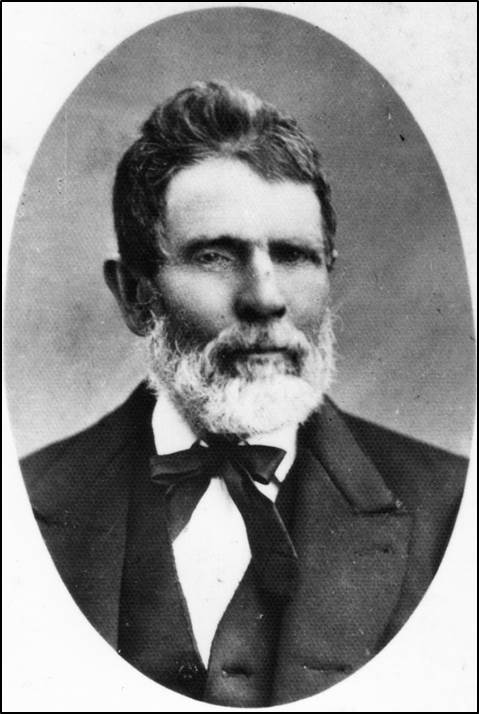

John Hudson Robbins

The details of the 1862 trip were recorded by William Chambers (elected as captain of the wagon train) in a journal, later give to John ‘s son William Arthur Robbins, who copied and edited parts of it. Robbins descendant Marjory Cole generously provided a typescript copy of this journal to me many years ago. It is important to remember that the journal has gone through some editing and may not reflect Chambers daily entries exactly as he wrote them.

The party left Floris, Davis County, Iowa, on April 14, 1862 and intercepted the Oregon Trail near Kirkville, Missouri. Their first days out were not easy. Within one week John had replaced his lame cow for an iron gray pony called “Lightening.” Encountering the flooding Medicine Creek (in Missouri) on April 28, the emigrants had some difficulty in crossing that stream. It was only after considerable effort were they able to get the wagons and stock across the creek. Two days and 38 miles of further rough riding induced the journal author to write: “Never again will I laugh at my grandmother for sitting on a pillow.”

On May 3 they encountered “two miles of canvas covered wagons slowly moving like soldiers going to war.” The Robbins and Chambers party attempted to pass the other wagon trains but failed, leaving three lengthy caravans in front of them. It had been decided to bypass St. Joseph but they had to take on more supplies and repair the wagons, so they camped about three miles out of town. In town, all the men bought “six-shooters” as they were warned about the Indians they would meet on the trail west.

After stocking up on supplies the party headed west on the Oregon Trail. By May 18 they had reached the Big Blue River in Nebraska – probably not far from where their Robbins cousins had died ten years before. In fact, they passed a number of graves in this area and several of the company were ill with what they called “plains cholera.”

Capt. Chambers wrote on May 27:

Last night we had a dance in the new covered bridge across the Little Blue River. John Robbins played the violin and called the dances. About midnight a party of eight men on horseback demanded that we vacate the bridge so the could cross. After crossing, they came back and dance with us until daylight.

The emigrants stopped at Ft. Kearney to inquire about Indian conditions on the trail and the following day they crossed the Platte River with surprisingly little difficulty, having been warned of the quicksand that had caught emigrants before. On June 12 they passed the famous Chimney Rock and Court House Rock, but the following day they had to remain in camp due to dysentery among the emigrants. The doctor in the caravan (Dr. Thomas A. McBride) treated them with “burnt flour.”

The Robbins and Chambers families arrived in Ft. Laramie on June 18. There they again restocked their supplies (and camped northwest of the famous fort. Crossing the North Platte River on June 27, the pioneers lost two calves and a horse in the swift water. The river was too deep to ford so everything had to be ferried across. Once across the river and onto the high, dry country of Wyoming, they encountered poison water again and had difficulty keeping the cattle and horses from drinking it.

On Sunday, June 29, the party reached Independence Rock, where they read the names of previous emigrants scratched and cut into the surface and undoubtedly added their own. A few days later (July 3) the party came upon a small settlement where the people had gathered to celebrate Independence Day. On the 4th Dr. McBride read the Declaration of Independence, Capt. Chambers delivered the oration, and John Robbins sang and led the choir. French traders roasted a steer in an open pit which provided the dinner. It was learned that the steer had been stolen from a previous wagon train. After all the wrestling, pistol and rifle contest, and all the eating was finished, they went to a nearby house and danced until daylight. John Robbins was head fiddler and caller.

Camp on the Oregon Trail

In the following weeks the emigrants were plagued by Indians. On July 7, Shoshone Indians visited the evening campsite wishing to trade horses, gamble, beg and steal. Two days later the party camped near a trading post, where the Indians tried every means they could to obtain alcohol, even offering to trade their wives or children.

After years of hard use the Oregon Trail was marked by deep ruts which the wagons would frequently get stuck in. Hot and thirsty, the cattle frequently gave out in the arid lands of Wyoming and Idaho. Steep hills were another problem. In descending a steep ridge called the “Devil’s Backbone,” it was necessary to lock the wagon’s wheels and everyone had to walk down, with the exception of the driver. At the bottom of the “Devil’s Backbone” the party came across five fresh graves of a family that had been killed in a runaway wagon the month before.

On July 15, the Chambers-Robbins party had some excitement in the trial of Dixie Johnson. As written in the Chambers journal, Dixie Johnson was a miner returning from California.

The previous night the California party enticed a number of Shoshone squaws into their camp and after they had imbibed a large amount of fire water, Dixie Johnson engaged in a quarrel with another member of the party, claiming that he was attempting to steal Johnson’s squaw. As a result of the argument, Johnson stabbed and killed the other member of the party. A jury was impaneled and Johnson was tried and found guilty of murder. The volunteer judge sentenced Johnson to be shot by one member of the jury. Each of the six jurors was given a rifle, only one of which was loaded, the five other guns containing blanks. The murderer was then taken over a hill beyond the camp, stood up against a tree, and the six men pointed their guns at his heart and fired. Johnson refused to be blindfolded or tied and smiled at his executioners and gave the order to fire. He was buried under the tree with a headboard stating ‘Here lies Dixie Johnson, murderer, who died July 15, 1862.

Upon reaching the Portneuf River the party was disheartened to find that they were short of funds to pay for a ferry crossing. For a plug of tobacco, however, they were able to get a trapper to lead them to an easy fording place. A couple of days later they arrived at Fort Hall, which was not in the condition they expected. The buildings were quite shabby and traders ran the fort, serving the passing trappers, Indians, and emigrants.

On July 29 they reached a campsite on the Snake River where they had been told they could catch salmon.

They limbered up their fishing tackle, and soon succeeded in catching a large supply of salmon which were making their way from the Pacific Ocean to the headwaters of the Snake River to spawn. The salmon were badly bruised by jumping over falls and riffles in the lower snake River and were really unfit for human consumption. The party had been living for many days off of side meat and were very anxious to secure fresh meat to replenish their depleted larders. They ate an excess of salmon, which made many members of the party ill…

Other hazards awaited the party. On August 21 one of the oxen died after being bitten by a rattlesnake. That night most of the emigrants slept in the wagons and not on the ground as they usually did. The trail they were following alongside the Snake River was narrow; occasionally cattle or horses would slip off the narrow trail to their death. Once, a wagon train almost tipped over, lodging against a rock. Three hours later, the men were finally able to pull it upright.

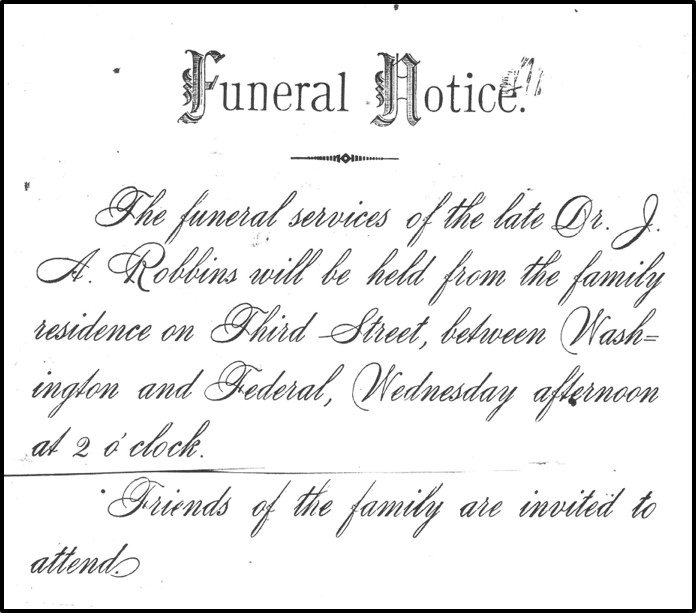

On September 12 tragedy struck. Hester Robbins, wife of John, died after giving birth to a still-born daughter. Hester had been sick since July 29 with salmon poisoning. Hester and her daughter were buried in a wagon box on a “knoll overlooking the Powder River Valley.” The grave was marked by a stone cairn and wooden head board. At the same time this terrible event occurred, John Robbins’ last team of oxen died.

Part of the wagon train decided to remain in the Powder River valley while John Robbins was able to obtain a team of oxen to help carry him through to the Willamette Valley. He and his small children started out once again on September 17th.

On Sunday, September 21, the party caught up with three of the preceding wagon trains in the Blue Mountains, where they were preparing to hold church services. As the journal author wrote:

John Robbins was asked to lead the choir, but declined, saying that he felt that he could never sing again. Dr. Withers, a Campbellite minister, told of the death of Hester Robbins and infant daughter, and preached a sermon dealing with the passing of the pioneer mother and baby. At the conclusion of the services, there was not a dry eye in the party.

After descending the Blue Mountains into the Umatilla country, the wagon train followed the south bank of the Columbia River to The Dalles. John Robbins and his children took the river route to Portland, arriving in that city in late September. It is likely that he was met by his brother Lindsay Robbins or perhaps some of the other Robbins cousins in the Willamette Valley. And there, in the Pacific Northwest, began part two of John Hudson Robbins’ life.

(Jacob Robbins-Absalom Robbins-John Robbins-John Hudson Robbins)

Norval next appears in the stories as causing the wagon train to slow or stop due to illness not long after the family left their wintering place in Missouri. His oldest brother, William Franklin Robbins, later wrote a long story that was published in the Decatur Press the following year: “We started from Randolph county, Missouri, the 15th day of April last, (1852.) Brother Norval was sick, and we had to lay by with him, one place or another, near two weeks, before we reached the Missouri river.” This was supported by cattle drive John N. Lewis’ diary entries which recorded on April 20th of that year “this day we laid in camp on the account of Norvel Robbins being sick” and on the following day “his day we crost a very broken part of the country far about 7 m. and put up on the acount of Norvel being sick…”

Norval next appears in the stories as causing the wagon train to slow or stop due to illness not long after the family left their wintering place in Missouri. His oldest brother, William Franklin Robbins, later wrote a long story that was published in the Decatur Press the following year: “We started from Randolph county, Missouri, the 15th day of April last, (1852.) Brother Norval was sick, and we had to lay by with him, one place or another, near two weeks, before we reached the Missouri river.” This was supported by cattle drive John N. Lewis’ diary entries which recorded on April 20th of that year “this day we laid in camp on the account of Norvel Robbins being sick” and on the following day “his day we crost a very broken part of the country far about 7 m. and put up on the acount of Norvel being sick…”

and The Brazen Overlanders of 1845

and The Brazen Overlanders of 1845  by Donna Wojcik Montgomery (1976), look at the entirety of the 1845 emigration from Missouri to Oregon, and provide listings of every family they have identified as being on the Oregon Trail that year. Two more recent books take a slightly different approach. Wood, Water & Grass: Meek Cutoff of 1845 (2014)

by Donna Wojcik Montgomery (1976), look at the entirety of the 1845 emigration from Missouri to Oregon, and provide listings of every family they have identified as being on the Oregon Trail that year. Two more recent books take a slightly different approach. Wood, Water & Grass: Meek Cutoff of 1845 (2014)  by James H. and Theona Hambleton takes a very pro-Stephen Meek position, claiming that the mountain man, by virtue of his frequent fur trapping travels across Oregon, was never lost and knew exactly where he was at all times. This is a view not held by other researchers, including the group of researchers that came together to study and travel the Cutoff and who’s work is the basis for The Meek Cutoff: Tracing the Oregon Trail’s Lost Wagon Train of 1845 (2013)

by James H. and Theona Hambleton takes a very pro-Stephen Meek position, claiming that the mountain man, by virtue of his frequent fur trapping travels across Oregon, was never lost and knew exactly where he was at all times. This is a view not held by other researchers, including the group of researchers that came together to study and travel the Cutoff and who’s work is the basis for The Meek Cutoff: Tracing the Oregon Trail’s Lost Wagon Train of 1845 (2013)  by Brooks Geer Ragen. Anyone interested in the Cutoff is encouraged to find these books for the various perspectives they provide.

by Brooks Geer Ragen. Anyone interested in the Cutoff is encouraged to find these books for the various perspectives they provide.