Nathaniel Norval Robbins, usually called Norval but sometimes listed as N. N. or Nathaniel, was the youngest son of Dr. Nathaniel and Nancy Robbins, and was an Oregon Trail pioneer in 1852. Born in 1832 he started out on the trail as a teenager and upon arrival in Oregon City had just turned twenty years of age. He became one of the longest lived of all the pioneers.

His name comes up several times in the reminiscences and stories of the wagon train trek. The most entertaining, though somewhat fictional, was the story Destination Oregon written by his niece Kate (Sharp) Jones. Kate began her story with a reimagining of the Robbins family at breakfast during their last day in Decatur County. Here is an excerpt:

Early one morning in October, 1851, the family of Dr. Nathaniel and Nancy Robbins was seated around the breakfast table. It was to be the last meal in the comfortable big kitchen of their Indiana home. For on this day they were leaving it — leaving to join the great westward migration that was slowly wending its way over mountains, plains, and deserts toward the land of great promise, the Oregon Country, where they hoped to establish new farms and homes that might in time prove to be more prosperous and comfortable than the ones they were leaving behind.

A hearty meal had been prepared that morning by Zobeda and Nancy, the two younger daughters, a good old Hoosier family breakfast of griddle cakes made with buckwheat, honey fresh from the hives, sweet potatoes, and homemade sausage. Jane, the third daughter of the family, hovered around the table filling the heavy mugs with fresh sweet milk and urging them all to eat a good breakfast.

Norval, 17 years old and the youngest boy, ate only a few mouthfuls, then pushed back his chair and left the table. Taking his hat from a peg by the door, he danced a few steps around the kitchen, whistling a gay tune. “Don’t forget to bring my fiddle,” he called to the girls as he scooted through the door.

“What is Norval so excited about?” Mrs. Robbins asked, eyeing her husband suspiciously.

“I didn’t notice that he was unusually excited,” he answered her, “probably in a hurry to get his cattle yoked up.”

“Do you mean to say you have given that boy permission to drive a team of oxen all the way across the plains?” she asked looking worried.

“I mean to say he is going to make the attempt and I think he will succeed very well. Why, he has been breaking in oxen since he was 15 years old. Don’t worry about Norval, he will be a full fledged bull whacker by the time we cross the great mountains,” he answered, laughing at her concerns.

Norval next appears in the stories as causing the wagon train to slow or stop due to illness not long after the family left their wintering place in Missouri. His oldest brother, William Franklin Robbins, later wrote a long story that was published in the Decatur Press the following year: “We started from Randolph county, Missouri, the 15th day of April last, (1852.) Brother Norval was sick, and we had to lay by with him, one place or another, near two weeks, before we reached the Missouri river.” This was supported by cattle drive John N. Lewis’ diary entries which recorded on April 20th of that year “this day we laid in camp on the account of Norvel Robbins being sick” and on the following day “his day we crost a very broken part of the country far about 7 m. and put up on the acount of Norvel being sick…”

Norval next appears in the stories as causing the wagon train to slow or stop due to illness not long after the family left their wintering place in Missouri. His oldest brother, William Franklin Robbins, later wrote a long story that was published in the Decatur Press the following year: “We started from Randolph county, Missouri, the 15th day of April last, (1852.) Brother Norval was sick, and we had to lay by with him, one place or another, near two weeks, before we reached the Missouri river.” This was supported by cattle drive John N. Lewis’ diary entries which recorded on April 20th of that year “this day we laid in camp on the account of Norvel Robbins being sick” and on the following day “his day we crost a very broken part of the country far about 7 m. and put up on the acount of Norvel being sick…”

All of the accounts tell the story of a cattle stampede that occurred causing some of the wagons to overturn. Kate (Sharp) Jones reported a recovered Norval whose experience with oxen came in handy.

After a few days of travel the cattle were becoming more and more restless and hard to control. At last the leaders, a pair of sleek young steers, raised their heads, sniffed a few breaths of the cool, damp air and made a run for it. The others quickly followed. Many of the wagons were overturned, some on their sides and some bottom side up. The one in which Zobeda was riding with the two little orphaned boys, Norval and William Barnes, was one that turned completely over. They escaped, however, with only a few minor scratches and bruises. It was during the stampede that 17-year-old Norval proved his manhood. He ran in front of his cattle, whipped and lashed their heads and held them until they quieted down. His was the only team that was held back.

Kate also reported that both her uncles Norval and James were fiddle players and somewhere near the continental divide put on a concert: “One night when they made camp near the summit, the sky was so clear the stars and moon seemed close at hand. Norval and James brought out their fiddles. ‘We are going to serenade the moon and stars,’ they said, ‘we will probably never be any nearer to them.’” He was probably one of the several young members of the wagon train who inscribed their names on Chimney Rock, which they rode and walked out to after the wagons camped for the night by the Platte River.

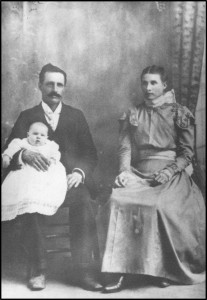

Norval and Permelia (Bird) Robbins

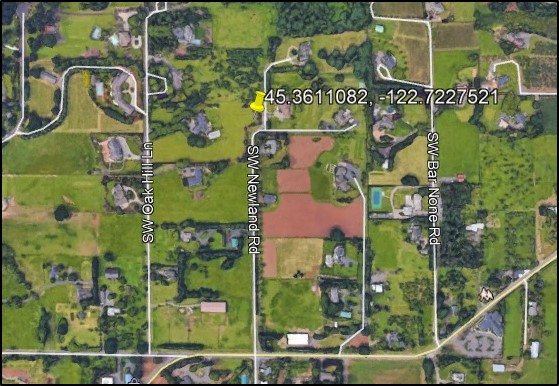

After the family arrived in Oregon, Norval took out a Donation Land Claim near other family members in the Stafford area, north and east of present-day Wilsonville. There he met and married Permelia Bird, a member of another pioneer family: she was the granddaughter of Robert Bird, the namesake for the Bird cemetery where many of the Robbins family are buried. The were married in the winter of 1858 and again Kate (Sharp) Jones has the story: “It was the coldest day they had seen in Oregon and Benjamin Athey, one of the wedding guests, remarked that he thought the Robbins and Birds were mating out of season, since the guests nearly froze on their way to the wedding.”

On October 15, 1855, Norval Robbins enlisted as a private in Samuel Stafford’s Company in the 1st Regiment of Oregon Mounted Volunteers. In his enlistment papers he was described as being six feet tall, with dark hair, hazel eyes, and light complexion. His occupation was given as farmer. Norval was sent to the Simcoe Valley in south central Washington where the Yakima Indian war was beginning. Years later in Norval’s pension application, a friend named Caspar Hinkle stated that Norval “received a wound or hurt of some character and was sent by the sergeant with me to Oregon City.” Norval saw little action, therefore, as he took sick on 22 November, a little more than a month after enlisting. He never missed a reunion of the Indian War veterans however!

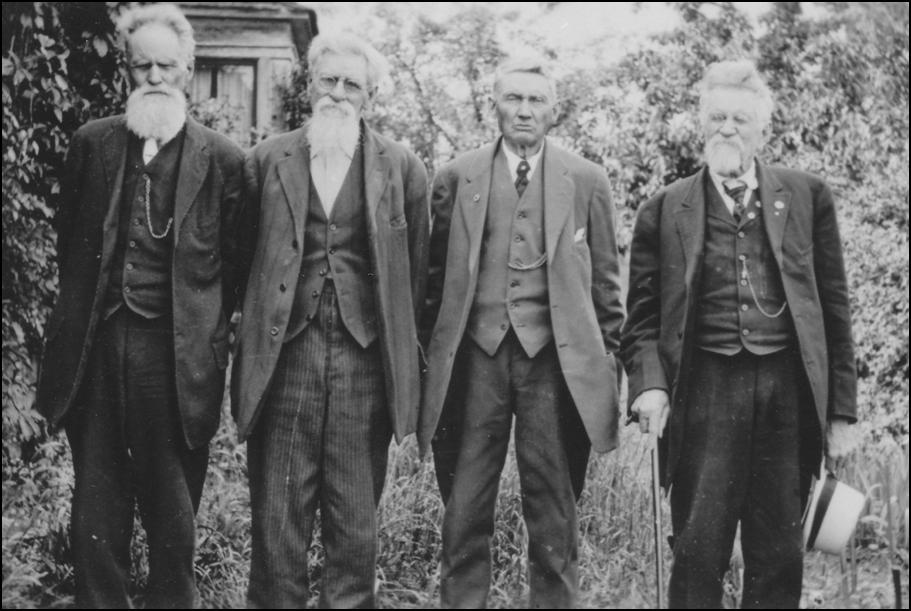

Norval and Permelia had five children, of whom four lived to adulthood. The oldest son was named Oren Decatur Robbins, in honor of his father’s birthplace. Next came Absalom Allen Robbins, named after a grandfather; little Absalom died at just under one year of age. Next in the family was Laura Leanna Robbins, then Christopher Carll Robbins, and finally Rufus Merritt Robbins. Oren, Laura, and Chris were married but only the latter two had children. Rufus died at the age of nineteen. You will note similarities between the names of Robbins family members in Oregon with those back in Indiana; the family carried their naming patterns with them.

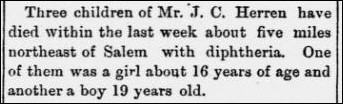

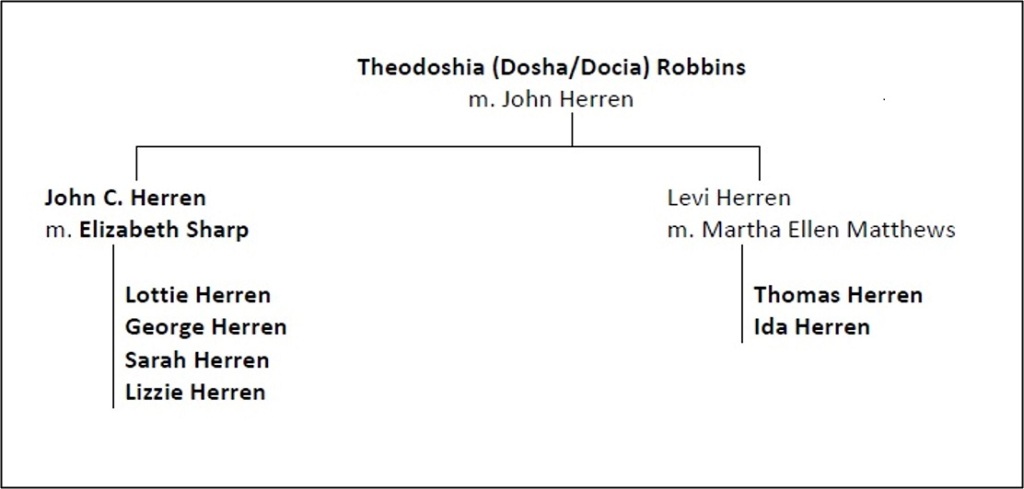

After living in the Stafford area until 1877, Norval and his family moved to eastern Oregon and were said to have settled about thirty-five miles east of Canyon City. When the Snakes, Bannocks, and other local Indians began attacking settlers Norval removed his family from area. They sought refuge at Heppner (perhaps with their Herren cousins?), and then returned to western Oregon for good. In 1880 they settled in Logan east of Oregon City.

Norval and Permelia (Bird) Robbins

In 1899, the following “personal mention” appeared in the Oregon City Enterprise:

“N. N. Robbins, janitor at the Barclay school had his leg broken on July 4th. He attended the celebration at Logan and during the day his horse got loose and in attempting to catch him Mr. Robbins was kicked on the leg with the above result.”

I have some notes compiled by Robbins family historian Margaret Davis who was able to interview Kate (Sharp) Jones, as well as Lulu (Kirchem) Ward and Irene (Kirchem) Doust, granddaughters of Norval, in the 1960s. Among the stories are the following, which provide a small flavor of the man.

Norval was a great practical joker, but like many practical jokers he couldn’t take a joke on himself. He loved to tease his grandsons. One day two of his grandsons tied a crow in a tree and ran yelling in the house for grandpa to get his gun. Norval came running and shot the bird. When it didn’t fall from the tree he realized he had been part of a ‘joke’, but he didn’t think it was very funny.

Another time he had been having trouble with animals getting his chickens. Hearing a ruckus one day he went running to the chicken coop, where by the noise coming from the coop he realized that the animal was still inside. Permelia had followed him and kept yelling at him not to get near as she was sure it wasn’t a weasel but a skunk, but, Norval was down on his stomach reaching into the hole to pull the animal out. It was a very sad Norval a few minutes later when he found to his regret that it wasn’t a weasel but a very potent skunk.

Norval Robbins, the tough pioneer that he was, died on Christmas Eve 1926 at the age of 94, while his steadfast wife Permelia lived until 1932, dying at the age of 93. Both are buried in the cemetery named for her grandfather, the Robert Bird Cemetery.

(Jacob Robbins-William/Absalom Robbins-Nathaniel/Nancy Robbins-Nathaniel Norval Robbins)

Norval next appears in the stories as causing the wagon train to slow or stop due to illness not long after the family left their wintering place in Missouri. His oldest brother, William Franklin Robbins, later wrote a long story that was published in the Decatur Press the following year: “We started from Randolph county, Missouri, the 15th day of April last, (1852.) Brother Norval was sick, and we had to lay by with him, one place or another, near two weeks, before we reached the Missouri river.” This was supported by cattle drive John N. Lewis’ diary entries which recorded on April 20th of that year “this day we laid in camp on the account of Norvel Robbins being sick” and on the following day “his day we crost a very broken part of the country far about 7 m. and put up on the acount of Norvel being sick…”

Norval next appears in the stories as causing the wagon train to slow or stop due to illness not long after the family left their wintering place in Missouri. His oldest brother, William Franklin Robbins, later wrote a long story that was published in the Decatur Press the following year: “We started from Randolph county, Missouri, the 15th day of April last, (1852.) Brother Norval was sick, and we had to lay by with him, one place or another, near two weeks, before we reached the Missouri river.” This was supported by cattle drive John N. Lewis’ diary entries which recorded on April 20th of that year “this day we laid in camp on the account of Norvel Robbins being sick” and on the following day “his day we crost a very broken part of the country far about 7 m. and put up on the acount of Norvel being sick…”