Dow and George, the two youngest sons of William Franklin Robbins, worked and lived near each other for much of their lives, and will be discussed together in this post. Both of the boys came across the Oregon Trail at a very young age.

Benjamin Dow Robbins was born in 1843 in Decatur County, Indiana, the fourth child, but third son of William F. and Melvina (Myers) Robbins. His older siblings were Nat, Margaret, and Gilman. Younger siblings were Nancy Adeline and Sarah Jane, and then George Henry, who was born in 1849 also in Decatur County. Melissa Robbins came along in 1851 just months before the family crossed the continent, and once in Oregon, Artemissa Robbins was born in 1855.

Dow was about 11 years of age when the family moved to Oregon, while George was about 3 years old. Neither boy appears in family reminiscences of crossing the plains. Mentions of “Dow” in their father’s Oregon Trail letter refer to William’s brother, John Dow Robbins, not his young son. It must have been an overwhelming experience, moving from comfortable farms and surrounded by family in Decatur County, to creaking along in wagons across arid plains, with the terror of sudden death at the hand of disease or Indians always ever present in their minds. Near the end of their journey Dow and George lost two of their siblings from disease. George may have been three years old at the time of the trip, but as an elderly man he regaled my mother with stories about the trek (and being a child it never occurred to her to take notes!).

In the 1850s William Robbins and his family lived along the Clackamas/Washington county line, near what is today Tualatin. Sadly William was killed in a hunting accident in 1856, and in 1859, the widow Melvina married Robert Lavery. Even though the children eventually went their separates ways in adulthood they all seemed to have a close connection, as census records and group photos demonstrate.

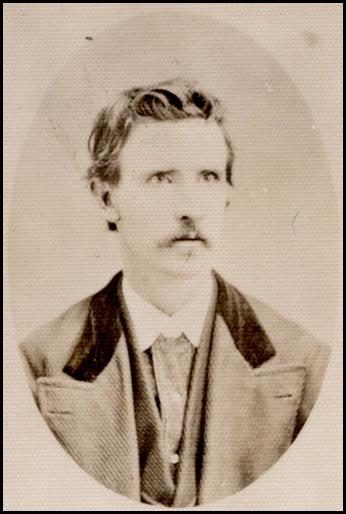

Dow Robbins

Dow Robbins has only been found in a few of the federal censuses. Williams’ family is not found in the 1850 census, where the family should have been living in Decatur County, Indiana. In 1860 Dow is living with his sister Margaret and her husband Isaac Ball, while ten years later in 1870 he is listed in the household of his oldest brother Nat, mother Melvina, full siblings George and Artemissa, and his half-sister Olive (Melvina’s daughter with her second husband).

Dow Robbins

We know that he was in eastern Oregon (Grant county) by 1879 because he appears in the local newspaper as having drawn jury duty. Between 1883 and 1890 Dow purchased many acres of ranch land in Grant county between the small settlement of Long Creek and the community of Hamilton, which was the home of his uncle John H. Hamilton. Some of the land was purchased directly from Hamilton.

In 1903, at the age of 59, Dow was married to Anna Maria Born, the daughter of a Prussian miner and farmer, and the couple had three children, Otis, Aura, and Erma, all born in Grant county. I had the pleasure of meeting and interviewing Otis and Aura back in the 1980s. They were able to provide some of the information about the family included in this post. Not finding Dow in the 1900 census, he appears finally in 1910 with his wife and children, with his brother George Robbins living them. About that same year Dow sold his ranch and became a partner in a livery stable in Long Creek, possibly with his brother George. Soon after Dow became ill, sold out his share of the livery, and moved in with his in-laws near the little town of Fox (Fox is miniscule and according to his death certificate he lived in Trester, which is a few miles west, and mainly a wide spot on the road). Dow died in 1916 of liver cancer, leaving his wife of thirteen years and three young children. He is buried in the Hamilton cemetery.

George Robbins

It’s unfortunate that we don’t have more information about the interesting life of George Henry Robbins, the future elderly raconteur and entertainer of younger generations.

George Robbins

He first appears in the 1860 census, where he is listed with his mother Melvina, sisters Adeline, Melissa, and Artemissa, half-sister Olive Lavery, stepfather Robert Lavery, and step-siblings James, Mary, John, Joseph, and Rachel Lavery. In 1870, when he was 21 years old, he appears in the household of Jesse Boone as a laborer. Boone was responsible for “Boone’s Ferry” across the Willamette River, now a prominent road in the community of Wilsonville. George has not been found in the 1880 census.

His sister Artemissa, her husband Charles Thompson, and sister Melissa, with husband Jacob Kauffman, and their families, had moved to southeastern Washington about 1880, settling in the community of Waitsburg. According to family stories, George also moved to Washington at this time, possibly working as a farm laborer or running a livery stable. Artemissa soon returned to the Willamette Valley, while Melissa moved north to Ritzville, but by 1900 George was still in the general area working as a farm laborer. He was also reportedly herding sheep in central Oregon, around the now-ghost town of Shaniko. It was there that he supposedly carved a small smiling figure in a casket which has been passed down in my family.

Carving by George Robbins

By 1910, George Robbins was living with his brother Dow and his family in the small community of Long Creek, where at age 60 he did “odd jobs.” When Dow sold out the livery stable, George reportedly took over a homestead near Hamilton and went to work for his neighbor Curtis Jackson.

After Dow’s death in 1916, George returned to the Willamette Valley where in 1920 he was living with his sister Nancy Adeline Ball in Tigard, Oregon, where, at age 70, he is listed as a “laborer farm helper.” The last census he appeared in was 1930 where he was staying with his sister Artemissa Thompson, along with her sons Roy and Clarence. A photo exists from 1928 which shows George Robbins along with his siblings with his siblings Artemissa and Adeline, until he finally passed away in 1940 at the age of 90. He is buried in the Winona Cemetery in Tualatin.

Uncle George Robbins

At George Robbins’ death there was one remaining survivor of the 1852 wagon train: sister Melissa (Robbins) Kauffman. More about her in a future post.

(Jacob Robbins-William Robbins/Absalom Robbins-Nathaniel Robbins/Nancy Robbins-William Franklin Robbins-Benjamin Dow Robbins & George Henry Robbins)

In Oregon there was a debate during the 1857 Constitutional Convention as to whether a married woman’s property act should be among its provisions. Matthew Deady, later a conservative federal judge, was against the idea. He said the act made “two persons of the husband and wife,” and caused “family alienation.” Delazon Smith retorted that it was not ownership of property that led to divorce, it “was the want of affection—the want of marriage of the heart.” The best response was Frederick Waymire who said “If we should legislate for any class it should be for the women of this [Oregon] country. They worked harder than anybody else in it.” The upshot was that the provision protecting women’s property was included in the constitution.

In Oregon there was a debate during the 1857 Constitutional Convention as to whether a married woman’s property act should be among its provisions. Matthew Deady, later a conservative federal judge, was against the idea. He said the act made “two persons of the husband and wife,” and caused “family alienation.” Delazon Smith retorted that it was not ownership of property that led to divorce, it “was the want of affection—the want of marriage of the heart.” The best response was Frederick Waymire who said “If we should legislate for any class it should be for the women of this [Oregon] country. They worked harder than anybody else in it.” The upshot was that the provision protecting women’s property was included in the constitution.