You don’t have to research the Robbins family very long before you notice some first-names were used over and over again. Even familiarity with the outline of the family doesn’t prevent confusion in trying to determine if it one Jacob Robbins or another which appears in a record.

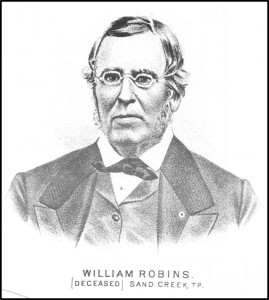

William “Spectacle Billy” Robbins

Some of the names are common ones: Jacob, William, Absalom, John, and Nathaniel, Nancy, Mary (or Polly), Elizabeth and Catherine. Some names are less common, but still got repeated frequently: Marmaduke, Micajah, Harrison, Norval, Bethiah, Theodoshia, and Mahala.

Early family historian William F. Robbins wrote about the naming patterns in the family and how nicknames were given to tell people apart from one another:

“Owing to the custom of giving one of the sons the name of the father, there came to be much confusion of names and many nicknames were used to distinguish them. William the elder was “Old Billy,” and his son was known as “Spectacle Billy.” Then there was “Rock Creek Billy,” Uncle Nat’s William, and Wilcord. Of the Johns there were “Old Johnnie,” “Rockcreek Bill’s John,” “Big Toe Jake’s John,” “John Henry,” “George’s Johnnie,” “Absolem’s John,” and Charity’s John Alex Purvis. Of Jakes there were “Big Toe Jake,” “Oregon Jake,” “Old Billy’s Jacob,” “Buddy Jake,” and “William Anderson’s Jake.” These names were not given in derision but to designate the person meant. This confusion of names still persists as witness: Will H., Will S., Will M., George William, Will F., William Riley, and William. Three men were known as Hence. Dry Jake and “Aunt” Jim came from Scott County about 1849, and unless they are sons of the Uncle Jim referred to, there is no place in the family circle to which they can be assigned. The name Hence is no doubt a corruption of Henry. Dry Jake is said to have been so named because of want of moisture in his system, he neither spit nor sweat. Aunt Jim earned his title by marrying a woman many years his senior who had already acquired the title of “Aunt.”

Some of these in the history we can clearly identify, others not so much. For today, let’s take a look at some of the William Robbins’s. “Old Billy” was William Robbins (1761-1834) while his son William (sometimes listed with a middle initial “B”) was “Spectacle Billy” (1797-1868), who apparently wore spectacles. “Rock Creek Billy” (1801-1864) was the son of Jacob Robbins II, thus a nephew to “Old Billy” and a first cousin of “Spectacle Billy.” “Uncle Nat’s William” was William Franklin Robbins (1816-1856) who moved to Oregon in 1852. “Wilcord” has not been identified, at least by me (perhaps a reader of this blog knows who that is?).

We know of at least four “William Riley” Robbins’s and possibly more: one was the son of “Rock Creek Billy” and his wife Elizabeth (Ferguson), one was the son of Jacob F. and Catherine (Myers) Robbins, another was the son of William Lewis and Mary Ann (Ferguson) Robbins, and John and Mary (Deweese) Robbins of neighboring Jennings County also had a William Riley Robbins.

Job Robbins and wife were the father of a William R. Robbins, as was John and Matilda (Barnes) Robbins, John Henry and Catherine (Ferguson) Robbins, and Jacob and Nancy Robbins of Scott County. What do you bet each were really William Riley Robbins?

All of these William Robbins were related. Today we struggle to sort them out and wonder if they knew each other. Of course they did. They had close relationships: father and son, uncle and nephew, first cousins, and second cousins, who all lived closely together. The various nicknames helped identify them.

As I compile these family stories I’ll try to indicate which William or Jacob or Absalom I’m talking about!