The Herren Family Cemetery is an interesting one – for many, many years you needed to get a state prison official to escort you to the cemetery. The reason being: the property was owned by the State of Oregon and was used by the Oregon State Penitentiary’s as part of their Farm Annex.

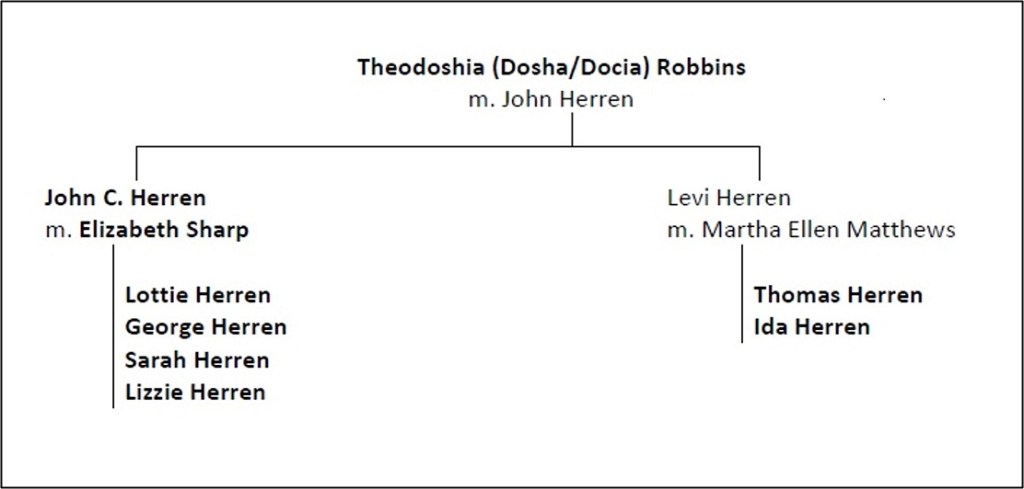

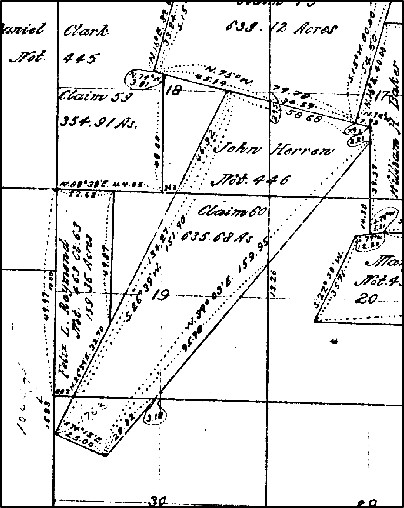

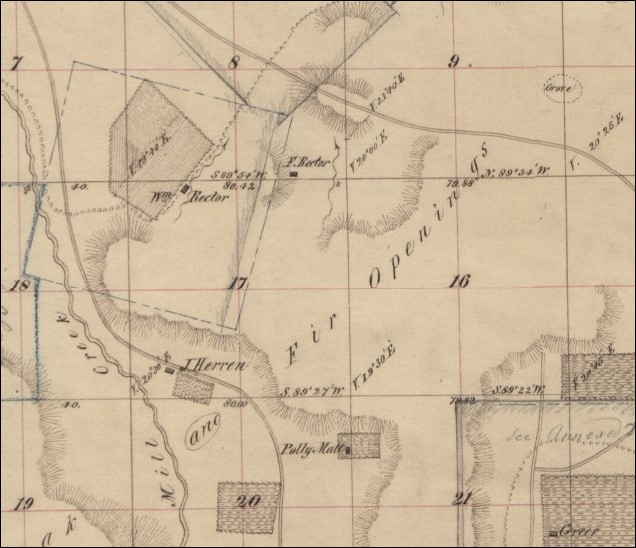

Let’s go back to the beginning. The Herren cemetery was established on the original 635-acre Donation Land Claim of John and Theodoshia (“Dosha”) (Robbins) Herren. The Herrens were first to come west, crossing the Oregon Trail in 1845, and notably took the disastrous Meek Cut-off across Central Oregon. You can read by this couple here and their trip here.

The strangely oblong shaped piece of land that John and Dosha settled on was southeast of the city of Salem, and included part of a ridge – overlooking the future site of the Oregon State Penitentiary to the north and overlooking Mill Creek and the future site of Turner to the south. An early survey map even marks the Herren house along the Salem to Turner road.

On the ridge above their house was the Herren cemetery. The earliest burial seems to be that of John Herren himself, who died in March of 1864. Several grandchildren, Charles C. Herren in 1868, Olevia Herren in 1874, and Nannie Welch in 1872 were also buried there. Dosha (Robbins) Herren died in 1881 and was buried beside her husband John.

Over the years more family followed, including William Jackson Herren (1891) and his wife Nancy Evaline (1905), Elizabeth Columbia (Herren) Hastay (1881, seemingly unmarked), James R. Herren (1887), Levi M. Herren (1914), and additional grandchildren. At least one nephew of John Herren, Joseph Garrison, was also buried in the cemetery in 1867.

The Herren family is said to have sold some or all of their property to the state. I have yet to identify when this occurred but the Oregon State Reform School first operated near the cemetery beginning in 1891. After the school moved in 1929, it operated as the Farm Annex of the Oregon State Penitentiary

from 1929 to 1990. Farm operations were gradually phased out at the site until it closed its doors permanently in 2021. A news article from 2022 states:

“In 1889 the State purchased the land for a reform school, the Oregon State Training School for Boys. After that relocated, the Oregon State Penitentiary began developing a farm annex in 19289, using forced prison labor to raise sheep, pigs, turkeys, rabbits, bees, and crops. By 1959 the State had expanded the farm to more than 2,089 acres. The State farm annex shut down over two decades ago, leaving much of the land unused, except for MCCI [Mill Creek Correctional Institution], a minimum-security prison, which was housed in the former reform school on a 390-acre chunk of the land. That site includes an unused cemetery from another previous owner of some of the land, the Heron (sic) family.”

In 2023 the property was sold to Clutch Industries, under the name Herron (sic) Crossing LLC. Before the sale, when it was initially announced that the state was going to be auctioning the property a descendant of another nearby original land owner claimed there were Native American remains buried nearby also. An online article states the following:

“A state archaeologist, John Pouley, said an agreement signed by DOC [Department of Corrections] and the Oregon Historic Preservation Office outlined precautions taken to consult with historic groups and local tribes. DOC spokeswoman Betty Bernt said there was “no evidence of human remains at the archaeological site other than the [Heron (sic) family] cemetery,” in which 20 graves are still visible from 1864 to 1922. She did not say what research was done to reach that conclusion.”

Being maintained by the Oregon State Penitentiary meant that the cemetery was well cared for. The prisoners who worked outside at the Farm Annex mowed the lawn, tended the iris beds, and kept the gravestones upright and in good condition.

When in 2023 the cemetery was sold to a private owner the condition changed. While the cemetery is supposedly open to the public you must cross the company’s private property to access it. Now instead of a prison escort you need to get a company escort. In the past the cemetery was well maintained. This is what it looks like today:

The grass is overgrown. The iris are lost in the weed thicket. Gravestones are laying over. The writing on the markers is starting to crumble. How much longer will this cemetery even be in existence? This isn’t the first cemetery our family has had to worry about, and sadly it won’t be the last.